The Link between the Study of Language and the Study of Literature

As someone who has taught both creative writing and linguistics, I've often been asked whether my linguistics training helps me to teach writing. The short answer is: no. The slightly longer answer is: not much. People usually don't find these answers very satisfying, so what follows is the even longer answer that I give to explain the other two.

Wikipedia Article on the Muses

Literature that isn't Amusing Isn't Literature

Linguistics is, or ought to be, a branch of science. It is supposed to take language apart, analyze it and see what makes it work. But literature is art, and it owes the majority of its power to the muse. Literature that is hacked together out of parts, without any inspiration is not literature. Literature, when it is read as if it were a crossword puzzle to be solved, will not be a-mus-ing, in the deepest, most etymological meaning of the word. Both the appreciation of literature and its creation require the intervention of a muse.

The Muses

Teaching X versus Teaching about X: A Question of Fluency

Teaching writing is not so different from teaching a language. (I've done both). It is significantly different from teaching something else -- say, history or political science or linguistics. This is because learning a new language or learning how to write has a strong practical requirement. I mean "practical" in its etymological sense. You have to practice. You have to actually do the thing you are learning. If you are taking French, you have to speak French. If you are learning how to write poetry, then you have to write a poem.

The study of history is completely different. When people study history they don't have to make history. They don't even have to discover history or rewrite history. They are mostly learning about facts. Occasionally they will analyze these facts, looking for coherent patterns, but they are never going to create any primary substance of their own in the process.

In history class you read history books and you write papers about history. In French class you speak French, you read French and you write -- not about French -- but in French. That's a big difference.

The study of linguistics is the the study of what language is and how it works. It can be very hands-on, and it requires an inspiration all its own. But linguists don't normally create their own languages, although, of course, that has been done, too! And when studying linguistics, people have to ignore all that is already automated and subconscious and fluid and inspired in their use of language, and break things down into parts, and try to see how they work.

Linguistics is about taking language outside its actual use, and slowing it down so that we can appreciate every step. It is the exact opposite of the acquisition of fluency. Some people are very good speakers, but they have trouble slowing the flow of language so that they can analyze it. Some people are very good at analysis, but have trouble with fluency.

Learning a new language is measured not just in terms of what you know, but also in how well you use your knowledge in real time. Language pedagogy is all about promoting fluency.

The same is true of teaching creative writing.

A prerequisite for teaching something is actually knowing the subject you are going to teach. A prerequisite for teaching how to do something is that you must be able to do it yourself. To teach fluency you have to model fluency.

My Job Talk at Providence University

In 1999, I was teaching both linguistics and creative writing at Tamsui Oxford University College in Tamsui, Taipei County, Taiwan. I was also interviewing for a position at Providence University, in Taichung County. Providence University was a Catholic four year college that was originally founded by missionary nuns in China. At the time it was a girls' school, and it had to be closed down when the communists took over. The school was eventually moved to Taiwan, still run by nuns, and in time became a co-ed four year college.

I had given one talk at Providence about linguistics, but when they called me in to interview, they asked me to talk about how my linguistics training came in handy in teaching creative writing. I was a little stumped by this request.

The Inspiration for My Talk: The Students and the Class

In one sense, the topic was rather an odd one for me to be speaking about.This was hardly a scholarly subject, and it was not in my supposed area of expertise. When the chairman of the department first emailed that she wanted me to talk about how I would go about teaching composition, perhaps drawing on my linguistics background, I felt a little crestfallen. That is, I wanted to be considered a linguist. I wanted to talk about my research. By the same token, if I were to talk about how I teach composition, it would have next to nothing to do with my linguistics background. I didn't use linguistic theory to teach composition. I drew on my experience as a writer, experience that I felt required to minimize in view of the fact that I hadn't been published. So I faced the prospect of this presentation with some misgiving, as I was afraid it was going to turn out to be one those really empty pedagogy presentations.

However, in the weeks that immediately preceded my interview, I derived a great deal of inspiration from my creative writing class. There were problems; there were issues; even the very personalities of the students suddenly gave me the impetus I needed to develop my theme.

One evening there was a playlet competition on campus, and one of my best students -- let's call her, for the purposes of this hub, Savannah-- wrote the winning playlet. However, while there was a prize for the director, best actor, best actress, costume and set design, there was no prize at all for the writing. There's something rather typical about that. Anyway, Savannah, spotting me in the audience, came during intermission and knelt before my seat and said: "Did you know I wrote our play?" All eagerness and anticipation mingled with pride.

"I thought that's what you said when you were up there," I replied. "But I wasn't sure. I couldn't understand most of what you said."

"Oh, they told me to speak only in Chinese," she said apologetically. "Personally, I thought that was rude..."

"No, that's all right. So what were you saying? Was it about how you put all these fairy tales together?"

"Yes. Did you like it?"

I nodded. "Very much. It was rather clever."

And then she changed her tack and said impetuously, referring to the current assignment in the creative writing class. "It's not fair that you're making us work in groups. It's not fair! I have to do all the work, none of them will do anything...!"

I smiled. "Yes, it isn't fair." Of course, it wasn't. It's just that there was no way that I could read forty-four separate novelas by the end of the semester.

"They are all saying that I am impossible to work with, that I think I'm so smart, but they don't do anything! I have to do all the work."

"Look, I would probably feel this way, too, if I were in your place," I replied. "But you have to work together on the outline, then each of you will be graded individually on the scenes you wrote. Don't do anybody else's work. Just do your part."

"But they don't do anything!"

"I will be questioning every person about his scene. I'll know if they didn't write it," I said.

That was on a Wednesday night. I stayed to see the prizes awarded for the playlets, which was probably a mistake, because I didn't get home and to bed until around 11:00 pm, and that was way past my bedtime. So the next day I had a bit of a headache.

Creative writing class was held every Thursday from 1:20 to 3:05 pm. On the15th, Savannah was absent. And her group, being forced to report without their prima dona leader, had to admit that they had done nothing -- no work at all on their project. (I asked each row to report on progress.)

"Savannah took the plot away with her," Lauren complained. "She said would do it all by herself. So we had nothing to work on." (I'm making up the names as I go along. Even though I knew them by English names that were not their true Chinese given names, I'm changing them to other English names, just to be on the safe side.)

"What do you mean she took the plot away?" I asked, perplexed. Plots being rather abstract concepts, it was difficult for me to grasp how one person's possession of a joint plot could deprive another person of knowledge or access to same.

"She took away the piece of paper," Lauren said, and the others nodded.

So then I started to give them a lecture how they were all jointly responsible and how they should all have copies.

But about then Selena and Maud from the last group, sitting to right of them, stirred, and Harold, their group leader, announced: "We made forty-five copies. Everyone had a copy." (I had made each of the groups come up with a plot summary which was then passed on to the next group to be worked into a sentence outline. )

"Oh, I see," I said. "So then I have a copy, too." At which the whole lot of them giggled.

Collaboration is not easy. I suspected there was some truth to both Savannah's complaint against her group members and theirs against her. And while I am not an advocate of group work in general, I think that we were all learning something from this.

Meanwhile, going over the other groups' plot outlines, I discovered that many of the so-called outlines were actually a synopsis disguised as an outline, by placing numbers at the beginning of every sentence, and placing each sentence on a new line. I commented on this, and then Selena came to see me during office hours. "I want to know what the difference is between a summary and an outline," she said.

I had told them in advance that every line should be one sentence and every sentence should consist of a single event. But I could see that this was not enough for Selena. So I started talking about cohesion -- how smoothly a summary fits together, and how abrupt each sentence in an outline is, without any discourse markers or anaphora. That is: no pronouns to refer to characters, no "and then" or "whereupon". Nothing to make things flow. Nothing to show how one sentence relates to the next.

"Oh, I see," Selena said seriously. "So in an outline the sentences don't have to be relevant!"

I laughed. "Yes, they have to be relevant. You just don't explain how they're relevant. You don't use words that help the reader understand what the relevance is. You're interested in the bare facts that describe the event. An outline isn't fun to read. It isn't pretty. It's just a tool."

Understanding dawned in her eyes. She thanked me and went away. And I too had learned something from this encounter, because I'd never before been asked to analyze the issue in quite that way. I had had implicit knowledge about this. Now it was explicit.

I woke in the middle of the night, excited with my new discovery, and knowing just what I would talk about at the Providence interview. But, of course, the next morning I had to teach linguistics IIA, and then in the afternoon, English conversation, and there were midterms to prepare and a filk for a fellow Rice graduate to polish, so that somehow I never got around to writing it up until the Sunday before the interview.

Calliope: The Muse of Heroic and Epic Poetry

The Day of the Talk

The talk that I actually gave differed only slightly from the talk I had prepared. "It has been suggested that I speak on how I teach advanced writing courses, perhaps using my linguistics background." At this, the Department Chair nodded her head.

"This semester I am teaching two sections of introductory linguistics, two sections of English conversation, an elective course called English Usage in Context, and Creative Writing. This last is the one advanced writing class I am teaching, so I think I will concentrate on it. This is a course for juniors and it is not an elective -- it's required.

"In one sense, having a creative writing course as an obligatory part of the curriculum strikes me as odd, since it seems appropriate to require all college graduates to have mastered certain writing skills, but it does not seem fair to require that they all be creative. Creativity is selective and unpredictable. So my approach to teaching the course is geared primarily toward the mechanics of writing fiction, not so much the aesthetics, and certainly not the inspirational, divine or music element. My grandfather, who was the rector of the university of Tel Aviv, used to say..." and here I said it in Hebrew first, then translated to English: "He said this of people disparagingly: `He's not music'. The word `musi' is not really Hebrew, it's borrowed from the Greek."

I glanced at the Classics Scholar in residence at this point, and I saw that he was gravely nodding his head, to acknowledge the etymology. But it suddenly occurred to me that he might feel insulted by this aspect of the talk. (This was a man who reportedly knew all of Herodotus by heart.) However, there was nothing left for me to do but plunge forward. I continued: "...meaning that the person's actions were not dictated by the muse -- (and this was a terrible put down.) But not everybody's music, and that's okay. We can however teach the mechanics and the skills necessary to create a workman-like product.

"Given that we can't require inspiration, the first semester of the course was devoted to diary-keeping. Skills in descriptive writing, dialogue, characterization and point of view were developed without requiring that the student invent anything. He could use the events unfolding before him and the characters he already saw all around him.

"While the students were engaged in this activity, I would give them lectures on various aspects of writing, and I suppose at this point I should describe on what parts of my background I drew in coming up with the material.

You might, for instance suppose, that my linguistic background would have provided me with a lot of helpful tools to deal with descriptive writing or narrative.

"Actually, the branch of linguistics that best deals with the topic is discourse analysis, and it is not my area of expertise. I did draw on some of the concepts from discourse analysis later on in the course, but my initial lectures, oddly enough, relied much more on my legal background.

"Students -- and maybe all people -- tend to rely on a lot of unsupported conclusory statements. So I would get a lot of descriptions along the lines of 'Joy is a beautiful, intelligent girl, full of life and concern for others.'

So I suggested to the students that they think of themselves as lay witnesses, unqualified to give an expert opinion, and that they stick to the facts. 'How do you know she's intelligent? Have you given her an IQ test? Are you qualified to administer such a test? What has she done that made her appear intelligent? What standard of aesthetics did you apply in determining she was beautiful? What does she actually look like? Could you describe her? How do you know she's concerned for others? Can you see into her mind? What facts can you dredge up that would support such a conclusion?'

"It wasn't so much that I was denying them the right to use an omniscient narrator -- although in the diary entries omniscience would be unlikely. Even if they could see into the character's mind, they had better describe the exact thoughts as they occurred, rather than coming to a general conclusion.

This requirement had to be drummed into them repeatedly, because it wasn't simply that their conclusions were unsupported, they were often at variance with the facts of the story they were telling.

"So for a very long time, the witness-in-a-court of law paradigm was the prevailing one, and it served us well. Now, when we got to dialogue, we did discuss turn-taking and the cooperative principle. (By the way, the handout on Queen Victoria and Charles Greville is from that phase of the course last semester when we were covering dialogue and point of view. That presentation went rather well, because they were able to figure out that even though the points of view were quite different in the two accounts, the two narrators were not really describing facts which were at variance. That is, they inhabited the same world and their accounts were consistent. Greville was censuring Victoria for being rather unsophisticated and ordinary -- but she never pretended to be anything else. Her self-characterization and his of her were consistent.)

"In fact, dialogue is one of the areas in which most of my students did pretty well relying on their intuitions. A detailed linguistic analysis was not required, since producing dialogue is not so different from engaging inordinary conversation.

"However, when during the second half of the first semester I required the students to come up with plots and plot outlines, a lot of structural problems came to the surface.

"Incidentally, this was a very traditional take on fiction and the short story form, requiring a plot with a gradual build-up, climax and denouement --and an integrated theme to go with the plot. I explained to the students that in some respects this is old-fashioned and perhaps out-dated, but that's whatI expected them to do in this class. The skills they acquire will serve them in good stead even if they decide to become modernists.

"Anyway, it turned out that they were pretty good at writing a synopsis or summary, but that they had real trouble coming up with the sorts of plot outlines that I required. What I asked of them was that they write an outline in which every line was a sentence, every sentence described a scene and every scene in the story appeared as a line in the outline. They had a terrible time adhering to this requirement.

"Now, I myself am not one of the world's greatest advocates of the outline method. I don't actually believe that every great work of art started with a fully realized balanced outline. When I was in school and I was required to work from an outline, I would write the composition first, and then I'd outline it. That's because I could write." At this point, I met the Department Chair's eyes, and I realized that I was perhaps treading on thin ice. That is, isn't that an arrogant assertion? But I tried to smooth it over and appear more modest as I continued: "When I did write the outline, it turned out that my composition had the required structure to begin with. So, as far as I'm concerned, an outline is just a tool we can use to ensure that the desired structure is in place: it is not an inviolable recipe for creating a composition. However, it's very helpful in order to discover where a work is deficient.

"Anyway, many of my students had a hard time coming up with all the required elements of a workable plot. But because they didn't understand how to write an outline, they often ended up with a synopsis that sounded pretty good and then a story that went nowhere.

"To give you an example of a story that I got last semester: John and Bob are friends. Bob is having problems with his girl friend. John and Bob go out to their favorite coffee shop,and Bob tells John that he and his girl friend are having problems. (The problems themselves are not described.) John says: "I have some advice for you." At this point, the typeface in the story changes, there are colorful headings and a list of twenty items, numbered and labelled, appears, in which a number of possible problems is enumerated and resolved. The student obviously got this list off the web, and it wasn't quite on point, since it dealt primarily with eating disorders, rather than relationship problems.

"The list goes on for several pages. Then Bob says: 'Thank you for your advice. Now I know what to do. My problem is solved. THE END.'

"Now, this is slightly amusing, but it is not music, and it is not a story. And while this was a pretty bad example, I had several others which were actually fairly well written on the whole, but which relied on the 'advice as plot point' scenario.

"Also, I found that some writers could write a story, but not an outline.

"So this semester, I had them exchange stories with somebody else and write an outline of the other person's story. This was preparatory to group work onnovelas in which scenes are assigned to different members of the group. Many of the students are still struggling with the outline form, even though they are working with rather sophisticated plots. In some cases, what they ended updoing was writing a reasonably detailed summary, and then numbering the sentences or paragraphs. When I pointed out to them, 'his is a summary, not an outline,' they were quite astonished. `What's the difference?'"

Very briefly, I allowed myself to look at the Clasics Scholar from the corner of my eye, and I could see that he was nodding, with a slight smile, and raising his eyebrows as if to say: "Good question."

I rather dramatically scratched my head, to indicate that this had required some thought on my part. "And oddly enough, this was where I had to draw on my background in linguistics to give them the answer: The difference is that a summary is high on cohesion, but low on detail. In an outline, discourse cohesion is practically nil, but each proposition is complete and self-contained. That means virtually no anaphora -- you repeat characters' names in the outline, you don't use pronouns, you don't use cover terms to describe several different actions, but instead you list each action or event separately. You do not use discourse markers such as `then', and `so' or`after which', and you do not use conclusions or summations.

"The students were satisfied. But I began to wonder why it was the issue of cohesion came out in what was essentially a meta-linguistic task. It wasn't about how they should write -- it was on how they should pre-write. Which is where my philosophy on teaching comes in," I added parenthetically. "It's a two way street. The students learn from me, and I learn from them. So I had to think about it.

"I suppose the answer is that discourse analysis is mostly an analysis of those things that come naturally. The students naturally wanted to make their output cohere. I had to explain cohesion to them in order to get them to engage in a less natural activity.

"Any form of analysis, such as outlining a story, or diagraming a sentence, or figuring out the scansion of a poem, is likely to draw on linguistic terminology and concepts. But the actual production of natural discourse does not -- which is why I seldom rely on linguistic terminology in those classes where the goal is fluency." I drew a long breath of air. "And at this point I'll open the floor to questions."

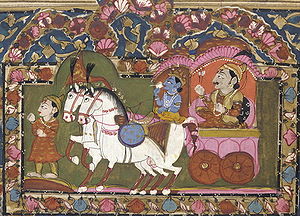

Arjuna and Krishna on the field of battle

The Baghavad Gita

Q & A

"What level are the students you teach in this course?" the local professor seated immediately to my left asked. (We were sitting in a circle.)

"They're juniors," I said. "Is that the kind of level you meant?"

"Yes," she said and then turned to some of the others and asked: "Is that the same thing we call 'junior' here?" When they had arrived at a consensus that it was, she started asking me about their level of English. "Are they all English majors?"

"Yes," I said, although after the fact I realized that a small minority weren't.

"And their English is good?"

"The level varies considerably. Part of the problem is that I had 46 of them last semester and 44 this semester -- that's because two failed. And that's a small class at TOUC. Because in some of my other classes I have about seventy. But it makes it very hard to teach composition with that size of class. Especially since my teaching style is very interactive."

The questioner's expression indicated that she,too, thought that was a bit too many and that I had her sympathy.

"Some of them are very good," I said. "Their English is excellent and they write well. And some of them have very poor command of English. And everyone else is someplace in between. But they're very motivated."

So there were several follow up questions to this from other faculty members asking about my methodology of dealing with those students who did not understand what I was saying at all.

After which, the Classics Scholar asked his question. He sort of raised his hand ever so slightly, in a very symbolic way, and the Department Chair motioned for him to speak.

"You made me think of the `Baghavad Gita'," he said.

"Did I?" I asked, feeling rather silly. "Well, I didn't mean to." I couldn't imagine what the Baghavad Gita had to do with anything I had said.

"The `Baghavad Gita' is an example where we're in the middle of a story, and suddenly there's this long bit of advice on how people should live their lives."

(When he said this, I suddenly saw his point, In The Bhagavad Gita, Arjuna is about to go into battle against his kinsmen, when, confused by his conflicting loyalties, he turns to his charioteer, who happens to be Krishna, and coincidentally the Lord of the Universe, to ask for advice. The greater part of the story consists of Krishna's philosophy concerning how best to live one's life. However, when we consider that the Bhagavad Gita is only a small part of an even bigger story, the Mahabharata, then maybe the ratio of advice to action isn't as high as it seems. If you want to know more about the Baghavad Gita, follow the link above.)

"So, when you were talking about that story that had the long list of advice in it, I suddenly thought of that," the Classics Scholar intoned. "Do you address that in your course? I mean, that there are different cultural expectations with regard to what the structure of a story should be like?"

I nodded. "Actually, this is an English language course, so the general idea is that we're learning how to write an English story -- or rather, a story in English, using the structural expectations of English speaking cultures." He nodded at this, and I went on: "But besides that, I explained to the students right from the outset that this is a rather old fashioned take on an integrated plot/theme." At this point I turned my attention from the Classics Scholar to the Department Chair, who seemed to be following what I said rather closely. "I explained that they would likely be asked to read Western literature that deviates from these standards. But I told them that if they learn the skills necessary to produce this kind of story, they will find them useful even if they later on choose a different, less structured form." The Department Chair nodded approvingly, and I turned my gaze back on the Classics Scholar. "So I think that pretty much covers all applicable aspects of cultural relativity."

The Classics Scholar seemed satisfied.

"Have you ever taught French?" a woman toward the middle of the local group asked. She was a French teacher herself.

"No, I never have," I replied. "You see, I got a B.A. in French and then right after that I went to law school. And we didn't do much with French in law school." At this, I perceived that Classics Scholar was laughing mildly to himself, but only very mildly. I continued speaking to the French teacher. "And after that, I praciticed law for nine years. So... My French is pretty rusty."

The kind and friendly woman to the far left said: "Many people want to practice law -- would like to very much. What made you decide not to?"

"Well," I replied, warming to my subject, "it's not that I'm not interested in the law. I would like to do some legal writing someday. And it's not that I don't appreciate the legal eduction that I received. But, I was a general practicioner in Grand Prairie, Texas, and that meant that I had to give people those services that they needed or wanted. And what they wanted was divorces. So, divorces is what I gave them."

They all seemed very amused by this reply, and laughter filled the room.

"Anyway, I didn't find that very fulfilling."

"Did you work for a firm?" the friendly woman wanted to know.

"No," I said. "I was independent."

There was a slight pause in the conversation and then people sort of gestured to me to look in the other direction, because Sister Agatha, (not her real name) sitting to my right, wanted to ask a question. "I have never written a story," Sister Agatha said, "but I think I would like to teach a creative writing course."

Sister Agatha was part of the old guard at Providence. There was a time when the school had been run primarily by nuns. That time was long past, and as a university chartered in Taiwan, Providence was now primarily in the hands of local academicians. Many of the older nuns did not have Ph.D.s, and they were either being sent state-side to complete this new requirement, or they were retiring. Sister Agatha was semi-retired, but she would still teach a course or so each semester, by her own choosing.

Sister Agatha was a kindly white-haired nun, and when I first visited the campus, she had smiled upon me in the most accepting way. I tried to compose myself into the most open-minded attitude I could muster. Although I sensed that she meant well, there was something odd about Sister Agatha's questions -- naive to the point of child-like simplicity. Before the interview began she had seen that I taught Biblical Hebrew on my CV, and she asked whether I could recommend a textbook, so she could teach it, too. I promised to email her the reference, and I didn't question her further. But it seemed odd to me that she would undertake to teach the course, if she didn't know any Hebrew. Now she wanted to teach creative writing, and she was openly admitting she'd never written any fiction.

"So my question is," she continued, "since I would not want to teach something unless I had done it myself, if I follow the directions you're suggesting, like using a sentence outline, then could I write a story?"

"Well..." I hedged, trying to be diplomatic about it, "if you follow the methodology I'm suggesting, creating a sentence outline, and building a plot with integrated theme, and you then proceed to write each of the scenes from your outline, being sure to use factual description and dialogue, then you will have a workable story. That is, a mechanically adequate story. But, of course, that's not all there is to writing, and using this method is not going to guarantee that your story is inpired or -- music."

"But what I want to know," Sister Agatha insisted, "is this how to write a story?"

"Well, no," I answered. "That's what I was trying to tell you about the difference between analysis and fluency. This is not the best way to go about writing a story. And in fact, I don't think that the great literary works that we read necessarily started this way. But if you want to make sure that yours measures up structurally, then outlining is a good methodology. It's just a diagnostic tool. It doesn't tell you what to write about. It's sort of like diagramming a sentence," I tried to explain. "If you want to make sure that a sentence structure is okay or if you want to understand how a sentence is put together, then you can diagram it. That's a good tool. But I am not suggesting that when speakers of a language produce a sentence, that's the process they go through."

The Department Chair seemed to be following my meaning. I could tell by her facial expression. But Sister Agatha still looked confused, so I tried a different example: "It's the same with poetry. If you think a great poem starts with somebody laboriously working out the meter he's going to use, and then deciding exactly how many stanzas there are going to be, well, that's way off. The muse comes, the person is hit by a bolt of lightening, the poem writes itself. However, once the smoke clears, upon further analysis, it turns out that it has a certain kind of meter. When the creative juices stop flowing, the poet may discover that his muse has handed him a slightly defective product, and he has to fix a few spots where it doesn't scan. That's why it helps if he understands meter formally, as well as intuitively. But a formal understanding of meter does not make someone a poet."

On the other side of the room, the only Taiwanese male propounded a question of his own. "It says here that you taught Biblical Hebrew for a number of years. How did you approach it? As theology or literature?"

"Neither," I replied, smiling. "I taught grammar." This evoked some merriment on the part of my audience. I went on to explain the way I taught Biblical Hebrew as a classical language and how that differed from the more conversational approach I used for Modern Hebrew.

Sister Agatha, however, was not quite done with her earlier question.

"What textbook did you use for the creative writing course?" she asked.

"I didn't use a textbook. I just put lectures together on the various aspects of writing: description, characterization, dialogue, theme, plot, point of view..."

"I've never taught creative writing," she repeated.

"Well, neither had I until this year," I said. That actually begged the question: what qualified me to do so? The thing that I was trying to keep in the background was my claim to literary merit. For all intents and purposes, my claim was unsubstantiated, and discretion was the better part of valor.

"I always find that I have trouble planning composition courses," Sister Agatha said.

I had to be sympathetic. "Yes, I had to rethink and restructure the course midway, also," I said. "Because I wasn't used to having so many students, so I assigned too much work."

"But you're saying that if I follow this method, I can write a short story?" she persisted, wrinkling her brow and looking worried.

"Well, yes. If you need to get a story written by Friday, then you can follow this procedure and you will have an adequate story. This won't make it inspired. There's no reason to suppose it will be a Pulitz..... a prize winning story. It probably won't move people to tears. But it will be adequate structurally and mechanically."

The interview went well. I got the job. But all the way home, I couldn't help thinking about Sister Agatha and her questions. I couldn't understand how a nun could be so oblivious to the idea of inspiration. Didn't she have a calling?

Didn't an angel appear before her and tell her to dedicate her life to this path? Did she suppose that every woman could be a nun, if only certain steps were followed, like a recipe? Didn't she realize that in order to write a good story you first of all needed to have something to say and a compulsive need to say it? Did she think that everything is based on formula? "Why," I wondered to myself, "are there so many religious people who have never been touched by the divine?"

The Muse and the Reader

Intervention by a muse is required not only for writing literature, but for reading it as well. I believe readers have to be inspired, too. When we have a good reading experience, we lose ourselves in the text. We are moved. Sometimes we get angry; sometimes we cry. We read with our whole bodies, not just with our minds. Poetry, to be experienced properly, has to be read aloud, and the cadence of it must course through every organ in our bodies. Poetry meant only for the eyes is not poetry.

Can literature be analyzed to good effect? Yes, but only by someone who has first experienced it viscerally. Which is why, to be a good critic, or just a good reader, you must be in touch with the muse.

To analyze something that you haven't felt is like trying to write a grammar of a language you don't understand. The grammar may seem very logical and organized, but how do you know that it's right, if you don't speak the language?